Poets are in season again in French museums. After an exhibition devoted to Michel Leiris, among others, at the Louvre in Metz, attention has shifted to Strasbourg, where Tristan Tzara is in the limelight. It is pleasing that museums should be reminding the public that not so long ago, in the 20th century, literary and visual creation went hand-in-hand, affording one another mutual support. In those days emerging movements were referred to as “avant-garde”. They defined themselves as much by their shared passion as their common opposition to certain things. They had political and moral convictions. Antisemitic graffiti on an artwork immediately prompted protests and petitions, even if the piece did not enjoy unanimous approval. This was a matter of principle. Viewing the exhibition devoted to the tireless Tzara, it is impossible to forget the present.

Tzara was born Samuel Rosenstock in Romania in 1896 and died a French citizen (naturalised in 1947) in 1963. The narrative of his angry outbursts and periods of revolt is told through his works, manuscripts, books, photographs and personal diaries. It resonates constantly: what you see on the walls relates to the content of the display cases, be it a famous piece by Jean Arp or Kurt Schwitters, the humblest scribbled draft or most elliptical postcard. Yet this is the biography of a man who took serious risks, aware that he was exposing himself to the enmity of others and disregarding any notion of compromise.

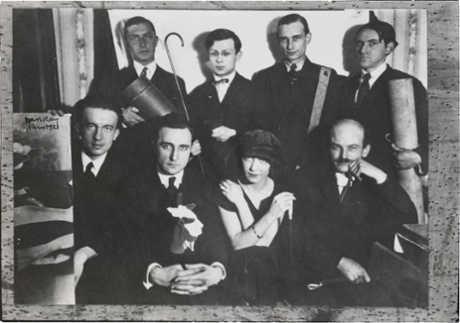

His friends – then former friends, then once again his friends and in some cases ultimately bitter enemies – had first-hand experience of his single-mindedness, particularly surrealist André Breton. Few people managed to stay on even terms with him from the Dada period to his death. In this respect Arp, Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, Pablo Picasso and Joan Miró were rare exceptions.

His life was marked by a series of paroxysms, which coincide with the darkest periods of 20th-century history. In 1915 he left Bucharest for neutral Switzerland, dodging conscription into the army. Adopting the name of Tzara, he settled in Zurich, and studied literature and philosophy. A few months later he became one of the founding members of the Dada movement, alongside his compatriot Marcel Janco and fellow refugees, mostly from Germany, including Emmy Hennings, Hugo Ball, Hans Richter and Richard Huelsenbeck. The rest of the story is now well known, taking in Cabaret Voltaire, a string of barely comprehensible poems, African chants, provocative dress and raucous parties.

It was Tzara who proclaimed that experimental art, Dada poetry and what was then called “art nègre” or “art primitif” were the vital ingredients in an explosive charge primed to blow away old rules and habits. As such he may be seen as both Dada’s theorist and head sapper – except that Dada would never have accepted a leader and Tzara rejected hierarchy or system.

From key creator of Dada, Tzara became one of its main spokesmen. After the first world war, the movement spread to New York, Paris, Cologne and Berlin. In January 1920,after months of correspondence and his first publications in French journals, Tzara arrived in Paris. He lodged with France and Gabrielle Picabia; Francis doing his portrait several times. He was involved in all that was happening in the city, with Breton and fellow surrealists, Philippe Soupault, Louis Aragon, Paul Éluard and Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes. But Breton’s tendency to dominate led to increasingly bitter disagreement. In September 1922, Tzara announced Dada was over and it was no surprise when he did not endorse the Manifeste du Surréalisme that Breton published in 1924.

Tzara returned to poetry, publishing collections illustrated with engravings by Juan Gris and Louis Marcoussis. He added to his collection of books, and African and Polynesian art. The architect Adolf Loos designed a house for him in Montmartre, enabling him to display paintings by his friends. Some of them are on view in Strasbourg, along with rare editions and a few of the masks and statues Tzara acquired.

In the early 1930s he started taking an interest in surrealism, while devoting much of his time – particularly his writing – to defending art nègre. But in 1935 he broke with Breton again, convinced that the struggle against nazism needed real fighters, not just intellectuals and that communism was the best response. He spent part of 1936 in Spain in a besieged Madrid, and in Valencia and Barcelona.

During the German occupation of France the “Communist Jew Rosenstock known as Tzara” lived in hiding in Lot, in the south-west, where he was involved with the local Resistance. A member of the underground National Writers’ Committee, he became one of its best known figures after the Liberation, joining the Communist party in 1947.

For once in his life Tzara belonged to an organisation. But in 1956, after the Soviet invasion of Hungary, he left. One of his final public acts was to sign the Manifesto of the 121 against the war in Algeria, in September 1960. The last major journey that he made was to Africa, which he had never seen despite his love of its art. In 1962 he attended the Congress of African Art and Culture in Salisbury, the capital of what was then Southern Rhodesia. Funnily enough, another French writer was there, Michel Leiris.

Tristan Tzara, l’Homme Approximatif is at the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Strasbourg, until 17 January 2016

This article appeared in Guardian Weekly, which incorporates material from Le Monde

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.