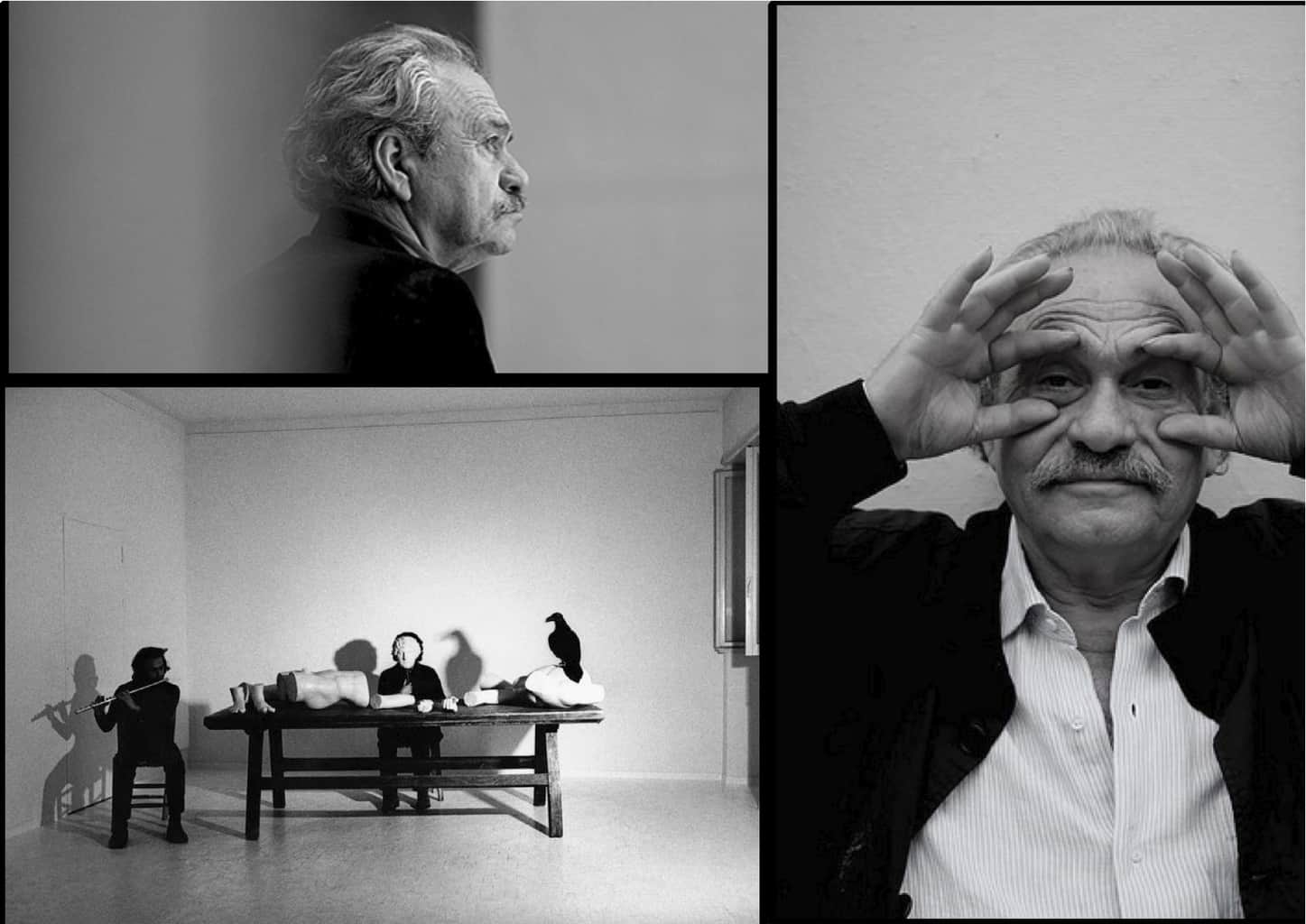

By Yorgos Karouzakis

You don’t need a reason to write about the internationally acclaimed Greek artist Jannis Kounellis.

Below is a brief glance at his life and artistic career from an interview I did in 2004 with the artist himself and with some of his closest friends. The interview was first published in Greek in Cover Story and Lifo magazines.

1936, Piraeus.

The buzz of travelers melds with the scent of coffee, oil and petrol on the waterfront. The hum of a diesel engine becomes one with the lapping of the waves on the briny body of a ship and the yellow aroma of lemons that the islanders bring into port. It was in such humble surroundings, near Kastella, that Jannis Kounellis was born – the birthplace he left behind in his 20s to move to Rome, newly married and in love with his first partner Effie, to the city in which he still lives today, the centre where he chose to begin his long journey through art.

A pioneer of arte povera, an artistic movement that emerged strongly in Italy in the turbulent 1960s, Kounellis currently ranks among the greatest artists of Europe and his work has been shown in major galleries and in some of the world’s greatest museums.

Ithaca is my mother.

Jannis Kounellis was born the year that dictator Ioannis Metaxas rose to power in Greece. He was just 10 years old at the end of the Second World War and it was not long before he felt the weight of the Greek Civil War: “the most brutal kind of war that anyone can experience,” he has said. “Civil war is the end of the concept of civilization,” Kounellis says. He spent his childhood and his adolescence in the shadow of this war, with an unformed sense of the destruction going on around him: a legacy of his birthplace that influenced the way he viewed the world and later shaped his art.

There is one reminder of tenderness from that period: two children holding hands pose for the camera in Piraeus at the late 30s. Only the eyes of the two boys betray the adults they would grow into: Jannis Kounellis and his childhood friend Yannis Sakellarakis, an acclaimed archaeologist, who died in 2010. “The photo was taken by my mother with a Leica from that period,” the archaeologist said in 2004.

A significant memory of their relationship comes from their teen years, when Kounellis’ family was forced by the war to make a sudden move from Kastella to Korydallos. “Those were dangerous days. My other grandfather lived near the Church of Profitis Ilias in Kastella, in the heart of the Civil War; no one could live there…,” Kounellis reminisced.

What Sakellarakis also recalled from his friendship with Kounellis, is the “dozens of times I climbed the stone steps to meet him in the laundry room. He would paint there, day and night. We would have endless discussions about Van Gogh. He was obsessed by the painter’s loneliness and agony.”

In a conversation with Bruno Cora in Paris in the 80s, Kounellis talked about Van Gogh: “The first artist I had a debt to was Van Gogh and I have not repaid it yet.” In our discussion, he defined Van Gogh as a radical and bold artist: “I really liked Van Gogh when I was in Greece. I loved his painting of the potatoes. There is something ideological about this painting, similar to my own piece of a pile of coal in a space.”

Sakellarakis cannot remember taking even a casual stroll with Kounellis: “He painted constantly. His eyes were often bloodshot in the morning from staying up the entire night before.”

Kounellis’ love and passion for art, however, had been repeatedly overlooked by the Greek School of Fine Arts and despite his persistent efforts he never made it in. “I had been painting since I was 13 years old. I sat the exams for School of the Fine Arts and failed. I was also a lousy student at school,” he admitted.

It was not just his passion for painting that had taken the small community of his neighborhood by surprise, but also his decision to marry his high-school sweetheart at the tender age of 17. Effie, whose family lived in a house rented by his grandmother, fell deeply and intensely in love with Kounellis, and so they married.

“I knew his first wife very well,” said Sakellarakis. “She was a beautiful, elegant girl. Their love was born at home, in our neighborhood. Their bond was quick and strong.”

“You fall in love easily when you’re 17,” Jannis Kounellis admitted with a smile. “It becomes harder to fall in love as you get older. I got married because it was a relationship of a lifetime.”

Seeking Renaissance

Like Picasso, Mondrian and Brancusi, Kounellis hungered to be in a place that would awaken his passion for what he loved best. The disturbing fact that people were killing each other at home and his failure to be admitted into the School of Fine Arts were not, it appears, the only reasons that prompted him to leave Greece. For Sakellarakis, there is a simple and poetic reason why he decided to move: “He wanted to see the world.”

American art critic Thomas McEvilley has a different interpretation as he writes about a young man whose desire for great things made him abandon his homeland in all its serene, mythological splendor. The artist’s journey, says McEvilley, was not a customary one; it was not a vacation. When Kounellis arrived in Rome, he swore not to speak Greek ever again and did not return to Greece for the next 20 years, according to the critic. When he actually started traveling back to his homeland, he did so for a couple of days at a time and solely for professional reasons.

“I don’t take oaths lightly,” Kounellis said in response to McEvilley’s interpretation. “It is a construct to explain my radical decision to leave the Byzantine tradition and to embrace the Renaissance. It had nothing to do with oaths… I never felt any bitterness toward Greece. I do not allow myself to be bitter in this way. I have a plan for the future. I was always trying to find the things I missed. There were no other feelings involved.”

Did you want to see the world? “You want to see the world so that you can, ultimately, discover what others are like. Not, of course, in the same way as a tourist, but like Odysseus. One leaves to see other centers. You can, of course, travel the world and still fail to see anything. Traveling is good when it functions like a step ladder that allows you to discover new lands. The important thing in the case of Odysseus leaving is not just that he went to war, but also that he returned. Returning is the good conundrum.”

His relationship with Greece began to sweeten in the mid-80s. In 1985, Vassilis Vassilikos met him in Rome, where the author had gone to live with his partner, Greek soprano Vasso Papantoniou. Later Kounellis, together with filmmaker Costa-Gavras, served as groomsmen for the couple. “I knew who he was and sought him out. At first he had some difficulties speaking Greek. I then thought that the best way to help him reconnect with the Greek language and with Greece was to conduct a lengthy interview for Greek television. We had the help of an amazing director, Mary Koutsouris, who admired Kounellis and his art,” said Vassilikos. “What Jannis found in Rome was the Renaissance and the ‘center’ that had been such a philosophical concern for him. The concept of a ‘center’ was evident first and foremost in Italy’s layout and architecture: every village and town has a ‘piazza.’ His entire philosophical quest boils down to the relationship between the measure and the Center.”

Katerina Koskina, an art historian and one of Jannis Kounellis’ few close friends in Athens, called his decision to live in Rome “a conscious choice”: “He had the vision to see the continuity of Greek philosophy in the Renaissance. In that respect, I see Kounellis as the quintessential Greek, a cornerstone of the concept of the European man who has the vision to discern the continuity of Greek civilization.

A “hole in the canvas”

Kounellis and his young wife moved to Rome three years after they were married and they both enrolled at the Accademia di Belle Arti. In this environment, Jannis Kounellis was reborn. At the age of 24 he showed his work for the first time at one of the most prestigious galleries in Rome, the Galleria della Tartaruga. De Kooning, Scarpitta, Burri and Fontana had all shown the work at the same space. His early works were canvases with letters, numbers and symbols, while that first exhibition (“L’ alfabeto di Kounellis”) shot him into the mainstream of the Italian art world, a world that he never left and in whose evolution he continued to participate.

The smell of the gathering storm of radical social movements poised to explode throughout the world scented the air in Rome. The Cultural Revolution in China, growing anti-war voices, the black liberation movement and the eruption of feminism in the United States, and the utopian fever that had taken grip of Europe in May 68 added strength to Kounellis’ personality and his work began reflecting his feelings for drastic political change as part of his quest for a new unit of measurement for a new social condition.

In the mid-1960s the Italian artist Lucio Fontana, adopting the view of Malevich, wrote: “I want to open us to space… So I make holes, infinity passes through them, light passes through them, there is no need to paint.” In this liberating climate for the arts, which also saw a strong presence from another major Italian artist, Alberto Burri, Jannis Kounellis laid the groundwork for the world he was to discover in the years to come.

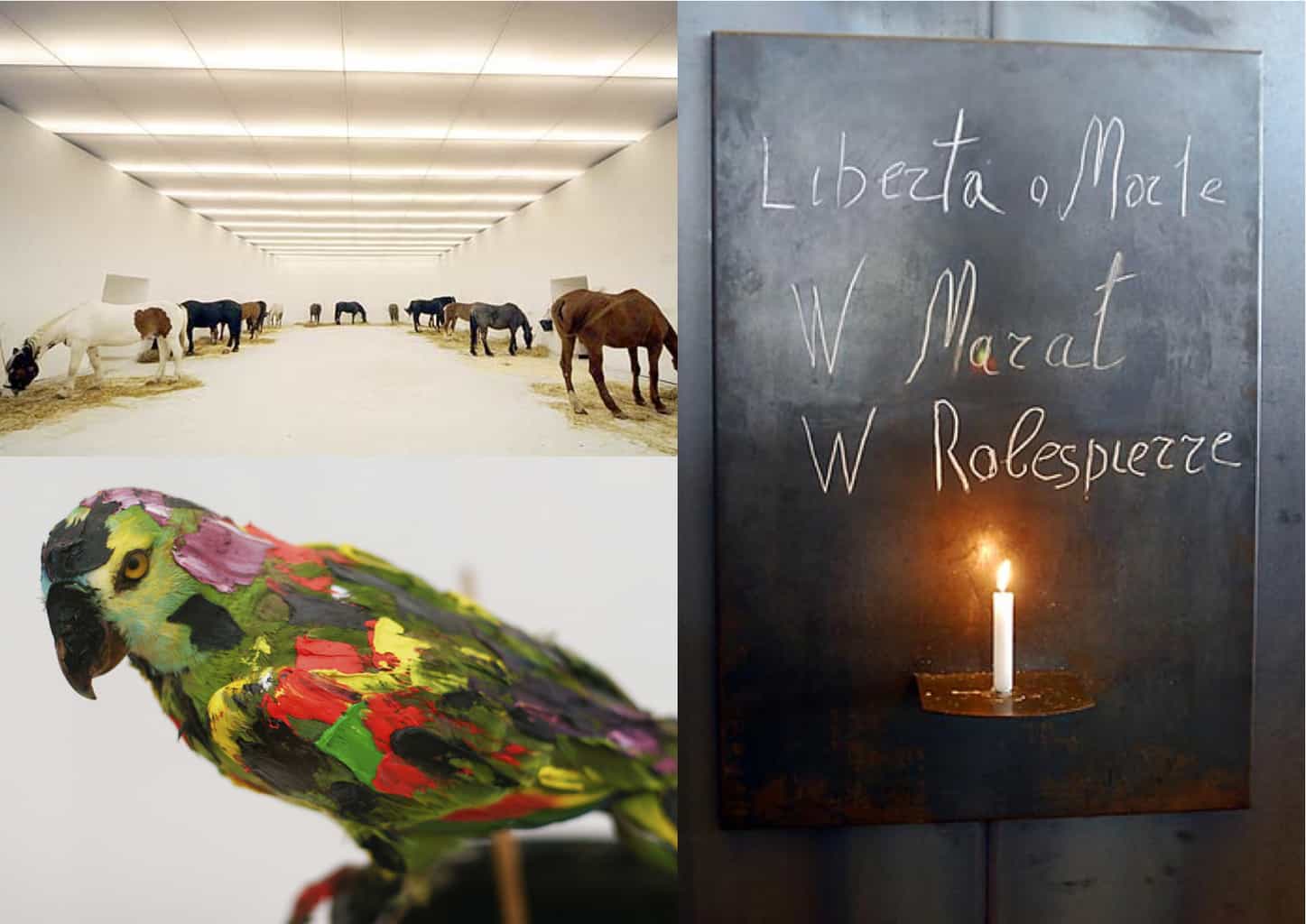

“A pivotal role was played in my development by the work of Burri and Fontana, as well as of many other artists of the same generation who found a path for their quests in their material. Later, political events inspired in us a reading of history that, without a doubt, had a major influence on our sensibilities and on the way that we evaluated space, allowing us to codify an idiom which, obviously, took into the account the historical and cultural concerns of this country,” Kounellis said. The artist encapsulated the fire that was burning at the time in a 1969 piece of black sheet metal. On it was written, in chalk, the names of Marat and Robespierre and right underneath the phrase: “Liberta o Morte” (Freedom or Death). A burning candle was placed on a small shelf that protruded from the panel. Art opening up to life.

From early on Kounellis’ art formed an unexpected bond with life. In one installation from 1967, shown at the Galleria L ‘Attico, he made a steel structure covered in cotton and vases painted with metallic paint, containing soil and cactuses. On a painted sheet metal frame on the wall he placed a perch and a real parrot. These were radical gestures, unique acts of theatricality, which led him two years later to present, at the same space, his flagship installation, which consisted of 12 horses tethered to the gallery’s walls. He recreated the installation for the 1967 Venice Biennale. The horses were not sculptures or symbols, but real live animals, with all their smells and sounds.

In this installation, art historian Rudi Fuchs saw a recreation of the scenes on the Parthenon frieze in Athens and at St Mark’s Basilica in Venice. He also discerned references to the paintings of Delacroix and Picasso. In an interview with Robin White, Jannis Kounellis said: “I always thought that my work with horses has to do with the spirit of the Enlightenment.”

When I later reminded him of the installation he offered a different interpretation: “The horses were tied to the wall of the gallery in order to make a connection between the living element and the idea of solid foundations such as those that that exist in homes. Their placement in the room delineated the building’s foundations. When an exhibition like this ends, all that remains is a memory. It is the same with a theatrical performance. And this was the significance of my action, which is defined by freedom. It is a vision designed on the principles of play staging.”

That same year Kounellis released live birds at the Kunsthalle in Dusseldorf. Later, at the Galleria L’Attico in Rome and at the Sonnabend Gallery in New York, he tried his hand at a quirky performance: he, as a living sculpture, on horseback, in the center of the gallery, with his faced covered by a plaster mask of Apollo: A subtle reference to and, perhaps, a nostalgic comment on the loss of the ancient world.

Jannis Kounellis’ appreciation for the dramatic arts grew through dynamic collaborations with great theater and opera directors such as Carlo Quartucci, Theodoros Terzopoulos, Tadashi Suzuki and Heiner Müller. In what was probably the greatest moment of his collaboration with Muller at the Deutsche Theater Berlin, two years after the fall of the Wall, he placed an “open wound” on the stage: a well-like opening from which emerged a metal cylinder filled with blood, while an arrangement of cupboards around the stage suggested memory and the brutality of a then-bygone era. It was the ideal setting for a performance about what is best forgotten following the collapse of East Germany.

The palpable truth of a sack and a lump of coal

Jannis Kounellis never stopped using unusual sites and buildings, moving in space like a traditional painter across the surface of a canvas, where humble materials, often elements of nature, are assigned the role of color. In a manner that is clearly taken from life he presents bags attached to steel hooks or objects piled up in front of door and windows, heightening a subtle sense of fear, of threat or of protest.

At times be becomes poetic, such as when he carried the wrecked hull of a ship into a museum for a work titled “Albatross” in an exhibition curated by Christos Ioakimidis in Berlin.

“In all of his work, he ‘paints’ with the modest yet tangible memory of a burlap sack, a lump of coal, a piece of discarded wood, a plaster copy of an ancient head, which leads him to create real images, as though he is abandoning the art painting of canvas and then coming back to it,” said Katerina Koskina during our talk. She also commented on the significance of the measure in Kounellis’ work: “Man is what he measures all else against. Every item he uses – the bed, the sack, the door and the window – have but one point of reference: man.”

Kounellis was passionate about the work of numerous other artists, such as the work of the legendary Russian painter Andrei Rublev, the secular orthodoxy of Kazimir Malevich and the bold brushstrokes of Jackson Pollock, whose roots Kounellis traces back to the frescoes of Masaccio.

“Pollock was the beginning. Before him the American style was colonial art. Pollock discovered a new area. His paintings function as a form of awakening for America and for his entire generation.”

Kounellis also writes and talks a lot about what he loves. He told Bruno Cora: “I like to cast my mind back on the ‘fauve’ Matisse and then see how he evolved. I love Matisse the colorist; after all Matisse loved Delacroix just as I do. I also like to think of Matisse in Morocco. As I like to think of Rimbaud in Ethiopia. I do not love the political exploitation of Matisse. We need to re-examine the avant-garde stance of the avant-garde. But we mustn’t forget that poets, like artists, are born with a new language.”

On the occasion of the exhibition “From the Europe of Old” at the Van Abbemuseum in the Netherlands in 1987, he wrote a text in the exhibition catalog that depicted his world: “I have never killed anybody, but I am prepared to do so if they trample on my right to freedom. I have never borrowed linguistic extracts, except out of necessity. I have only ever sought beauty. I measured distance through objectivity. I saw the sanctity of everyday objects. I believed in weight as the right form of measurement. I have loved phrases that depict virginity as the ultimate state of being. I have traveled difficult paths, through the woods, heading up the mountain. Lead, hair, clouds, Ursa Minor, which points North, the wind. I don’t know how to live outside the labyrinth of language. I love the olive tree, the vineyard and the wheat. I want to see the return of poetry through any means: through exercise, observation, solitude, speech, image and rebellion. Unsatisfied in perpetuity.”

Most of the people with whom we spoke about Jannis Kounellis describe a tight-lipped man who “breathes to work and works to breathe”: “He also hides immense tenderness,” added the director of the Greek National Museum of Contemporary Art, Anna Kafetsi, highlighting the poetic power of his work as it emerges through mature political thinking. “Art is his entire life,” agreed Katerina Koskina and Manolis Babousis, a photographer and associate of Kounellis, who also spoke also his sense of humor: “He has a sense of humor and a sense of self-deprecation. He gets the smallest detail in a split second. He is also very generous. He doesn’t sweat the little things. He wouldn’t care, for example, is someone stole his ideas or mimicked him. He has confidence in his work and feels free. He is kind and affable. But he can also be demanding and hard.”